Is Muscle Memory Real? An Answer According to Science

Many people fear that a few days without exercise is a step toward getting smaller, fatter, and weaker.

This mindset is particularly common among people who are new to lifting weights or who haven’t gained much muscle or strength to speak of, usually because they’re afraid to lose what little “aesthetics” they have.

Here’s the reality, though:

You’ll have to endure periods where you can’t train, whether due to injury, family commitments, a frantic work schedule, Covid lockdowns, or some other shenanigan.

And when this happens, you’ll probably notice two things:

- You don’t lose as much muscle or gain as much fat as you expected (or any).

- What little muscle you lose comes back much faster than it took to gain it in the first place.

This is largely thanks to a phenomenon known as muscle memory, which helps you regain lost muscle and strength much faster than gaining it from scratch.

In other words, even if you have to take a long time away from lifting weights, once you get back to training, you’ll quickly regain any size and strength you lost.

What causes muscle memory, though, how does it work, and how much muscle can it help you regain?

You’ll learn the answers to those questions and more in this article.

- What Is Muscle Memory?

- How Does Muscle Memory Work?

- Can Muscle Memory Help You Build New Muscle Faster?

- FAQ #1: What’s the definition of “muscle memory?”

- FAQ #2: Is muscle memory real?

- FAQ #3: How long does muscle memory last?

- FAQ #4: Does muscle have memory?

- FAQ #4: How do you improve muscle memory?

- FAQ #5: Can you do muscle memory exercises?

Table of Contents

What Is Muscle Memory?

Muscle memory describes the phenomenon of muscle fibers regaining size and strength faster than initially gaining them.

Basically, it refers to the fact that it’s much easier to regain lost muscle and strength than it is to build muscle and strength from scratch.

In other words, if you follow a good strength training program for a year and build a significant amount of muscle, then take a break from weightlifting and lose some of your gains, it will take you less time to regain the lost muscle when you start training again than it did to build it in the first place.

The same principle of “hard to gain, easier to regain” holds true for many other skills and physical processes. For instance . . .

- Regaining your aerobic capacity after a layoff is much easier than initially building it up.

- Relearning to ride a bike or ski or skate is much easier than learning these skills the first time, even decades later.

- Relearning to play a song on the piano is significantly easier than the first time you try.

You can think of muscle memory as a reward for the hard work you put into building muscle and strength. Do it once and it’ll be easier to do again for years and possibly decades down the road.

How Does Muscle Memory Work?

The idea of muscle memory was first scientifically documented in the early 90s. However, it wasn’t until two pioneering studies conducted by scientists at the University of Oslo in 2012 and 2013 that a firm theory of how muscle memory works was formed.

And that theory goes like this:

Most cells in the human body contain a nucleus.

You can think of the nucleus of a cell like its brain—it controls and regulates the cell’s activities.

This little brain can only handle so much information, though, and its limited computing capacity restricts its ability to grow larger (and thus engage in more activities).

Muscle cells are unique in that they can contain multiple nuclei—known as myonuclei—which carry the DNA that orchestrates the construction of new muscle proteins.

As muscle cells have multiple “brains,” they can grow significantly larger than most other cells in the body.

Each myonuclei can only manage so much cell, however, and this amount is referred to as its myonuclear domain. To continue getting bigger, then, a muscle cell must add more myonuclei.

The catch is muscle cells can’t produce myonuclei—they must take them from another kind of cell called a stem cell. Stem cells are special cells that can be developed into many different types of cells in the body.

There are many different kinds of stem cells in the body, but the kind most involved in muscle growth are referred to as satellite cells. These cells lie dormant near muscle cells and are recruited as needed to help heal and repair damaged muscle fibers.

Once called upon, satellite cells attach themselves to damaged muscle cells and donate their nuclei, which aids in repair and increases the cells’ potential for more size and strength.

(This is one of the processes that causes your muscles to get bigger and stronger when you lift weights.)

The theory goes that once a satellite cell has donated a nucleus to a muscle cell, it stays there forever.

This means you can regain muscle you’ve lost much quicker than you can gain muscle you never had because your muscle cells don’t need to recruit new satellite cells to grow back to their former glory. Instead, they can simply fire up the muscle building machinery that’s been lying dormant.

This theory about the mechanics of muscle memory prevailed for more or less a decade—however, a recent review of the literature questions whether it’s as ironclad as once believed.

In this study, researchers at Maastricht University parsed the results of 60 animal studies and 16 human studies. They found that the studies were hit or miss: about as many studies found that myonuclei do stick around in muscle cells when training ceases as found that they disappear.

If you unravel the study details a little further, though, you’ll find that most of the studies that failed to support the myonuclear domain theory were of lower quality than the ones that did support it. In other words, the more methodologically sound studies tended to show that myonuclei do stick around in muscle cells after the person (or animal) stopped working out.

Where does this leave us?

Until scientists conduct more high-quality research, our understanding of how muscle memory works will remain blurry.

That said, based on the current body of evidence, it’s reasonable to assume that myonuclei do play some role in muscle memory, even if we aren’t 100% sure what it is.

Can Muscle Memory Help You Build New Muscle Faster?

Part of the reason people new to weightlifting build muscle so quickly (“newbie gains”) is their bodies are highly sensitive to muscle damage.

Specifically, during the first 6-to-12 months of lifting, satellite cells are easily activated after workouts, resulting in large infusions of myonuclei into muscle cells.

The more muscle you gain, however, and the closer you approach your genetic potential for muscle growth, the more difficult it is to keep adding new nuclei to muscle cells.

The mechanism of satellite cell activation is one of the main culprits behind this unfortunate reality. As you build more muscle . . .

- The total amount of satellite cells available for recruitment decreases.

- You must do harder and harder workouts to produce enough muscle damage to convince satellite cells to donate their nuclei to muscle cells.

- The muscle damage that does occur results in less satellite cell activity

Some people believe there’s a way to “hack” this system, though.

It takes around three to four weeks without training for a muscle to begin atrophying (wasting away), but the additional myonuclei gained through training probably stick around longer than this.

Additionally, the bigger and more trained your muscles are, the fewer satellite cells are recruited in response to training and the less muscle you build over time.

The sixty-four thousand-dollar question, then, is this:

Could you build muscle faster if you included training breaks in your plan that were long enough to “resensitize” satellite cells to muscle damage but not so long as to result in muscle loss?

And the answer is . . . maybe.

While there’s little research looking at how this strategy might influence satellite cell activity per se, two studies conducted by scientists at The University of Tokyo show that people who take regular breaks from training (3-week breaks in these studies) gain the same amount of muscle and strength as people who train continuously for the same total length of time.

Unfortunately, both of these studies . . .

- Were done on beginners, so you’d expect them to gain muscle quickly and easily regardless of whether they took breaks. The same probably isn’t true for more advanced weightlifters.

- Didn’t show that people who take breaks gain more muscle, they showed that it can be equally effective as continuous training.

- Were short, so it’s impossible to say if the same would be true over the long term. Considering that volume and intensity are the two most important training factors in muscle growth, common sense dictates that dramatically reducing these (by taking several-week breaks every so often) over longer periods of time would result in less muscle gain, not more.

- May only have reported these findings because the participants who took breaks were more rested and enthusiastic for their workouts than the groups who trained continuously. If that’s the case, you can accomplish the same thing with regular deloads.

A more plausible yet still comforting conclusion from this research is you can be out of the gym for weeks at a time without having to worry much about losing gains.

That means you can enjoy that vacation with a guilt-free conscience. Or recover from that injury patiently. Or bend your energies to a sport for a bit while putting weightlifting on the backburner. Don’t worry. Your muscles will be ready for a quick and triumphant return.

FAQ #1: What’s the definition of “muscle memory?”

In the context of working out, muscle memory describes the phenomenon of muscle fibers regaining size and strength faster than gaining them in the first place.

In other words, it refers to the fact that it’s much easier to regain lost muscle and strength than it is to build muscle and strength from scratch.

For instance, if you follow a good strength training program for a year and build a significant amount of muscle, then take a break from weightlifting and lose some of your gains, it’ll take you less time to regain the lost muscle when you start training again than it did to build it initially.

FAQ #2: Is muscle memory real?

Yes, though we still don’t fully understand what’s going on inside your cells that makes it occur.

FAQ #3: How long does muscle memory last?

It’s not clear.

That said, the most recent human research suggests that muscle memory likely lasts for several years rather than several decades and almost certainly doesn’t last forever.

FAQ #4: Does muscle have memory?

Strictly speaking, no, muscles don’t have an ability to acquire, store, and retrieve information in the way that, say, your brain can.

When people refer to “muscle memory,” they’re normally talking about one of two things:

- The phenomenon of muscle fibers regaining size and strength faster than gaining them in the first place.

- The form of “procedural memory” that makes relearning a physical task (such as riding a bike) much easier than learning it the first time, even if you haven’t done the task for a long time.

While these aren’t technically types of memory, we use the word “memory” because it often seems as if your muscles “remember” how to do things that you’ve previously “taught” them to do (even though it’s really your brain that’s remembered the skill, and is just telling your muscles what to do).

FAQ #4: How do you improve muscle memory?

The best way to improve muscle memory in bodybuilding is to train consistently for several years. According to the myonuclei theory of muscle memory, this changes the cellular structure of your muscles, which makes it easier to regain any muscle and strength you lose after a period of detraining.

FAQ #5: Can you do muscle memory exercises?

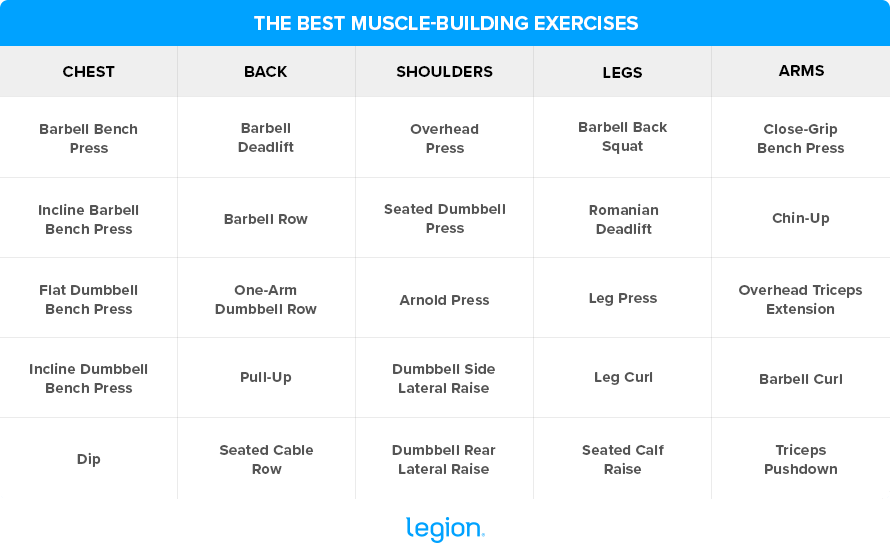

To make use of muscle memory you must first build muscle, which means the best “muscle memory exercises” are exercises that help you build muscle effectively.

Here are the best muscle-building exercises you can do for each major muscle group:

The post Is Muscle Memory Real? An Answer According to Science appeared first on Legion Athletics.

https://ift.tt/3ehRMzW December 22, 2021 at 06:00PM Legion Athletics

Comments

Post a Comment